London is a city crowded with voices, a place where countless words float about, colliding, competing, and often lost in the noise. For Hannah Stanislaus, poet and cultural organiser, the challenge has never been whether talent exists—it does, in abundance—but how it can be nurtured, sustained, and treated with dignity. Poetry, she argues, is bigger than any one individual’s rhythm or capacity, yet the structures surrounding it in Britain have long failed to allow it to breathe freely.

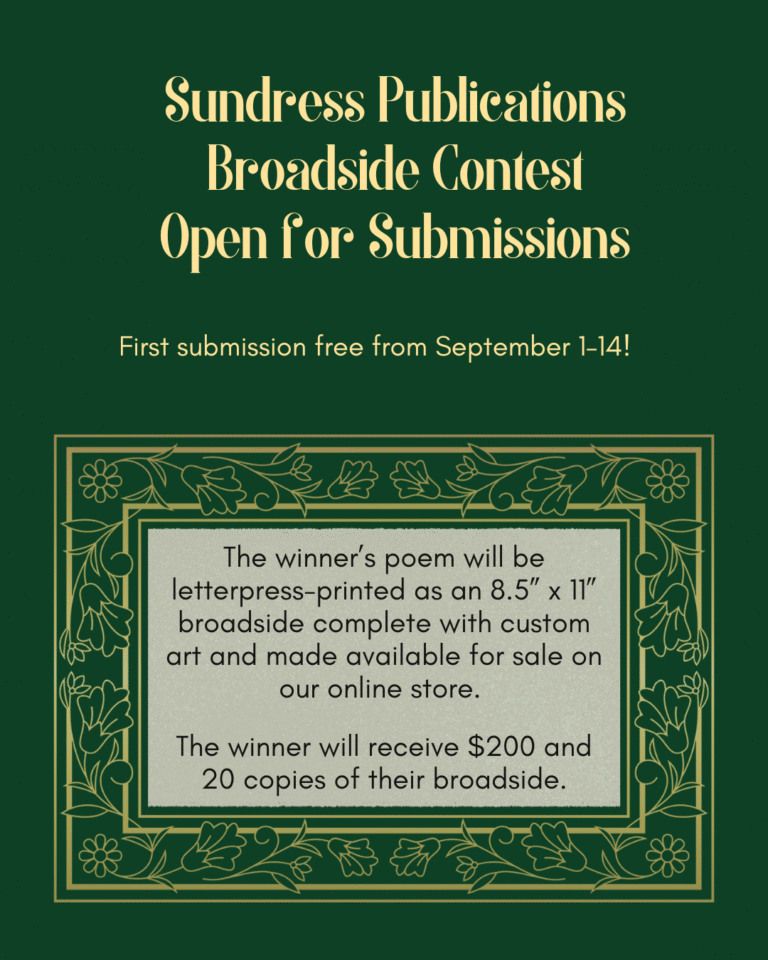

Making a living as a poet is precarious. “There’s not enough money to go around,” Hannah tells me, candid in her assessment. She has seen nights where poets are placed on pedestals, made “featured” in ways that fracture the community. “I don’t like to see one poet valued above another,” she explains. “Everyone should be treated with respect, not as though some belong and others don’t.”

Her frustration is not with nepotism, as some might assume, but with the deeper undercurrents of classism woven into Britain’s cultural fabric. Writers, she notes, are quietly sorted into boxes—by education, race, social standing, or simply by who they know. “In the United States,” she reflects, “poets are celebrated, treated like royalty. Here, too often, you’re met with: who are you?”

This comparison is more than wistful nostalgia. In America, Hannah is a two-time state slam champion. She has witnessed schoolchildren studying poetry as part of their curriculum, seen communities rally behind their artists, and stood in places where Black history is not erased but remembered. The statue of Phillis Wheatley—a former enslaved woman who became the first published African-American poet—stands in Boston as a daily reminder that Black voices matter. “That statue,” Hannah insists, “isn’t just for America. It should inspire every Black person to see themselves as valued.”

Her own journey into poetry began at seven, when she wrote a verse about a soft play area near Clapham Junction. At school, her headmaster asked her to read it aloud. That moment, small as it seemed, sowed the seed of performance. Decades later, with little institutional support and an underfunded arts sector, she still holds tight to that seed—watering it with her own resources, faith, and determination.

Lost Souls, the poetry collective Hannah founded, grew from this soil. What began as a church-supported gathering has now thrived for almost four years at The Exhibit Balham, running on loyalty, consistency, and the humble entry price of £3. “I’ve never gone to the Arts Council or the Lottery,” she admits. “The application process is exhausting, and rejection feels like a waste of energy. I’d rather pour my resources, with the help of my community, into creating a space where poets can grow.”

That choice is both radical and necessary. While government funding for the arts is meagre, money for war appears bottomless. “When it comes to bombs or fighter jets, there’s no cap,” she says sharply. “But when it’s art, when it’s culture, suddenly there are limits. What does that tell you about what they value?”

For Hannah, the answer has been to create her own infrastructure—spaces where emerging writers are not left behind. Lost Souls has become a hub for confidence, craft, and community. Ten of the poets under her wing are due to be published next year. It is proof, she says, that when the Black community unites rather than waits for recognition, remarkable things happen.

Still, the struggle for visibility in Britain continues. “If you think you know racism in England, you know nothing,” she cautions. While she acknowledges the freedom she has here compared to other parts of the world, she points out that England has no statues of historic Black figures, no public monuments to say: we were here, and we shaped this place too. For Hannah, the answer lies not in waiting but in building. “We need to create our own lists, our own legacies. No one is going to hand it to us.”

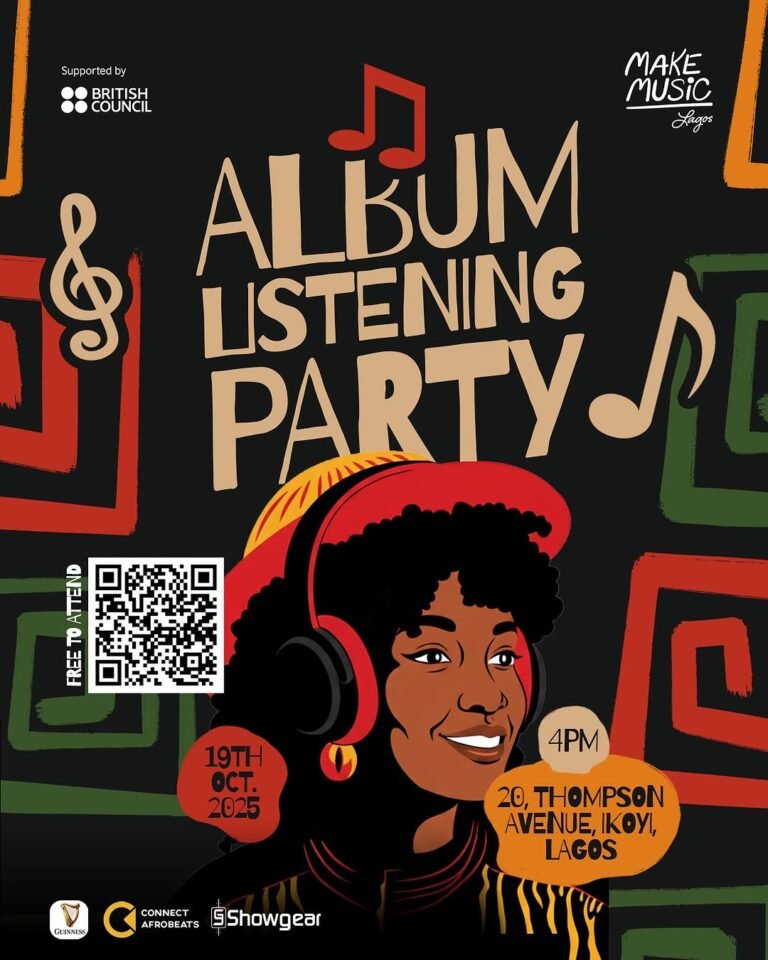

Her September calendar is evidence of that commitment: a charity poetry night for Hackney Night Shelter, a multicultural book fair at Conway Hall, and of course, the Lost Souls Sunday Slam in Balham. “It’s a busy, busy week,” she laughs, but behind the laughter is grit.

At the heart of it all is unity. “Many give up before even trying,” she tells me. “But as a community we can help ourselves grow. We don’t need to wait for the government or for gatekeepers to give us permission.”

In Hannah Stanislaus, you hear not just a poet’s voice but a call to arms—a reminder that Black art in Britain does not survive on recognition alone. It survives on resilience, on faith, on the belief that even when overlooked, you keep creating. You gather your people. You build your stage. And you let no one—no class system, no government budget—decide your worth.